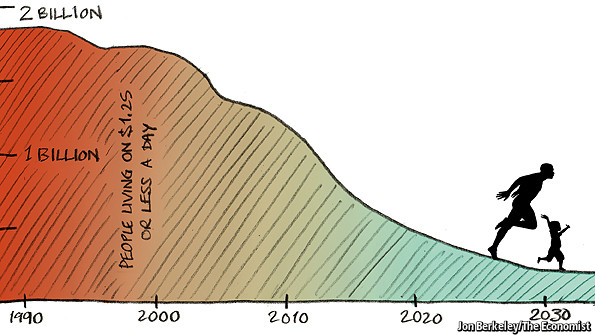

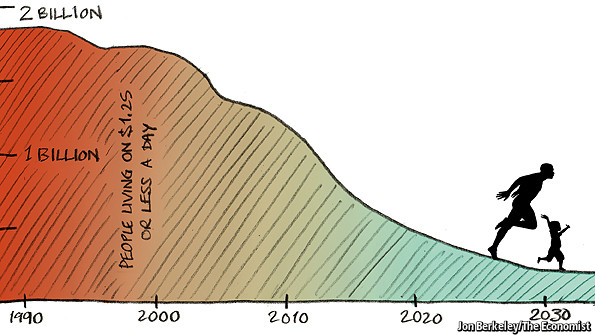

The world’s next great leap forward

Towards the end of poverty

Nearly 1 billion people have been taken out of extreme poverty in 20 years. The world should aim to do the same again

Libertarianism is a political philosophy that upholds individual liberty, especially freedom of expression and action. Libertarianism includes diverse beliefs and organizations, all advocating minimization of the state and sharing the goal of maximizing individual liberty and freedom.

But so far, i have not seen anything on the second most important

of the basic needs : Clothing

there is too much data on nutriciton deficiency, malnutrition, crisis in

agriculture, farmers sucides, food production, etc. But so far nothing

about clothing.

Clothing and textile industry has been allowed to evolve into full

fledged capitalistic model with economies of scale, etc after LPG.

Hence there is no supply constraints and prices too have

faller drastically when compared to the 70s and 60s. the poorest of

the poor are now better

and fully clothed than ever before. I guess for those who lived thru 50s, 60s

and 70s, witnessed torn and old cloths worn by poor and middle class.

Clothing was a luxury and owning terlin shirt was a prestige issue. Now,

a poor labourer can buy a piece of cloth (s shirt or saree) with his/ her one

or two day wages. I guess it cost more than these wage rates in the

olden days.

Can we have an informed debate about this ?

and land ceiling acts prevented Indian agricultre into evolving into full

fledged large corporate farms of 1000s of acres of size (or collective

farms of communist states). Only coffee and tea plantations have

been exemtped because they will not be viable on tiny or small

scale. But the logic behind allowing very large farms of coffee or

tea equally applies to other agriculture farms like paddy, wheat,

sugarcane, fruits, etc.

Any inputs about the comparisons between these two vital

needs : Food Vs Clothing in India ? I guess the entry of Reliance

made a big difference in this field..

Rajaji writes about Sri Sri Prakasa and Nehru's policies :

December 18, 1965 Swarajya

Source : Satayam Eva Jeyate Vol : III page : 170

Dated: August 05, 2009

Just five months ago, when stock and commodity markets hit rock bottom, capitalism was viewed as seriously if not terminally sick. The Financial Times ran a series of articles labeled "The Future of Capitalism." Economists, politicians, and philosophers saw the Great Recession of 2007-09 as a historic watershed, and produced new visions of a changed capitalism.

Today, that looks like much ado about nothing. Stock markets are booming, commodity prices are rising, and shipping rates have tripled. Pessimists warn of rising defaults in credit cards, commercial realty and corporate debt, so we could have a double-dip recession. But markets believe the worst is over. Despite political and public outrage over "casino capitalism" the financial reforms being contemplated across the world are not fundamental.

Four months ago, pundits waxed eloquent about learning lessons for reform from the financial crisis. Today the greatest lesson of all seems to be that capitalism, with all its flaws, can cope with Great Recessions. We have always had financial crises and always will: that's the nature of capitalism. The system will always need reforms to keep pace with changing technologies and innovations. Yet it has proved its resilience. Mark Twain once said that rumours of his death were greatly exaggerated. The same can be said of capitalism.

In years ahead, financial regulation will definitely increase. But this will change capitalism's profile only slightly, since the financial sector was the most regulated one even before the crisis. Hedge funds, the least regulated financial entities of all, survived the crisis without bailouts, even as banks, the most regulated entities, suffered badly. Regulation does not prevent all crises: Japan had the most regulated financial sector among developed countries but suffered a lost decade in the 1990s. Lesson: while the future will see more regulation, financial crises will still happen.

Stiffer capital adequacy norms look certain, to check the excessive leverage of the last decade. Yet history suggests that financial innovation will ultimately find ways round regulations. Bank regulation was ultimately circumvented by a shadow banking system, and off-balance sheet vehicles. Expect ultimate circumvention of the new regulations. This will not be entirely a tragedy. The gains of financial innovation may initially be eclipsed by losses, but the losses are typically checked after a fiasco whereas the gains become permanent.

In future, most derivatives will have to be traded through a clearing house, ending the counterparty risk that sank the asset-backed securities market. Despite criticism, securitization will continue with modifications. Banks will be able to securitise mortgages subject to retaining a certain proportion of mortgages they originate, a safeguard against excessive risk-taking in mortgage origination.

Some flaws will not be reformed at all. A special US problem is that its mortgages are non-recourse loans: the lender can get back the house after a default, but cannot go after the other assets of the borrower. This encourages massive willful default. Mortgage lenders in India, Europe and most countries, can go after other assets. But US politicians portray the entire housing bust as an evil perpetrated by lenders on innocent home buyers, and this political theatre avoids making borrowers accountable too. This carries the seeds of a future bust.

Politicians rail against excessive executive pay, and pay curbs have been instituted in companies being bailed out. Yet there is no move to fundamentally change payment structures in solvent companies. Some reformers want bonuses to be clawed back after a fall, but in many cases the employees may have left, and it is difficult to pinpoint accountability for innovations several years after they arise.

There is vague talk of reducing the global imbalances that exacerbated the crisis, but no sign of a credible remedy. Neither the IMF nor Financial Stability Forum have the requisite powers to check future imbalances. Asian countries still want to build high reserves as insurance, perpetuating global imbalances. This too has the seeds of a future bust.

Politicians want to check future bubbles, but are unclear how to do so. There will always be differing opinions on when exactly a boom becomes a bubble. Besides, bursting an asset bubble without damaging the overall economy is problematic. High interest rates will check a housing bubble, but will also hit corporates and consumers, and may cause a recession. Imposing stiff margin requirements to check a stock market bubble might drive money into other assets and cause bubbles there.

In sum, no major overhaul of capitalism seems on the cards. The rapid transition from despair in March to the stock market boom today suggests that the markets don't really see the need for great change. The existing system has survived the Great Recession, and that is seen as Great News.

Is this because humans are utterly myopic? No, moaning and groaning about the failings of capitalism are really part of political theatre in a recession. In my youth, the Communist Party would meet delightedly during every recession and proclaim that capitalism was now in its final death throes. Even after the collapse of communism, dirges are still sung by other parties. The singing ends abruptly as economies pick up again, and turns out to be more a recession ritual than an anthem for reform.

Recessions are viewed by the public as outcomes of policy blunders, as tragedies that cost jobs and production. That's certainly true. But recessions are also essential correctives to the excesses inbuilt in a capitalism system driven by animal spirits, innovation, the search for higher returns, and euphoria. The system works through creative destruction. This entails boom and bust, greed and failure, euphoria and panic, fast growth and recession. Recessions and financial crises may look like blemishes of capitalism, but are actually integral to its process of creative destruction.

So, even after reforms, expect more financial crises and recessions in the future. We would be wise to institute reforms that reduce the risks, but even wiser to understand that the risks cannot be ended without ending enterprise and innovation too.

http://swaminomics.org/articles/20090805.htm